Documentation is information about the code, as opposed to the code itself or the data that the code uses.

Documentation can take many forms, can be written manually or generated automatically, and is intended for many different consumers.

What kind of documentation is appropriate for those?

What kind of documentation is produced / consumed at those stages?

When analysing what a software should do, you come up with a set of requirements of what the program can expect as input, what its behavior should be, and what it should output.

Those can (and should, in any complex project) be written down as formal specifications.

Those can be seen as the earliest form of documentation of the software. They are often not set in stone, and are revised during development and integration.

As code is being written, the vast majority of programming languages allow inserting comments into code.

The purpose of comments is to put explanations together with code, to understand what the code does faster than just reading the code from scratch.

Such documentation makes explicit some implicit reasoning about code, e.g. requirements and behavior of specific pieces of code.

Sometimes in-code documentation is sufficient; but sometimes an external document outlining the code is beneficial. With proper documentation techniques,

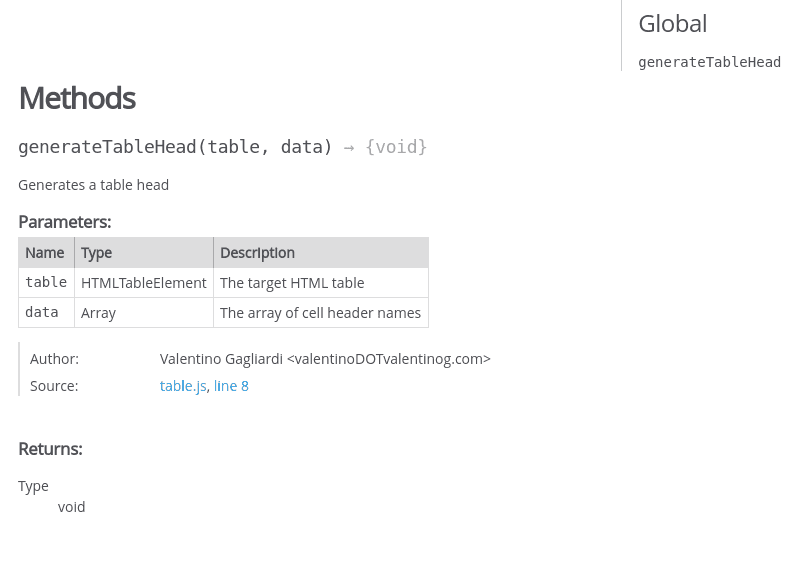

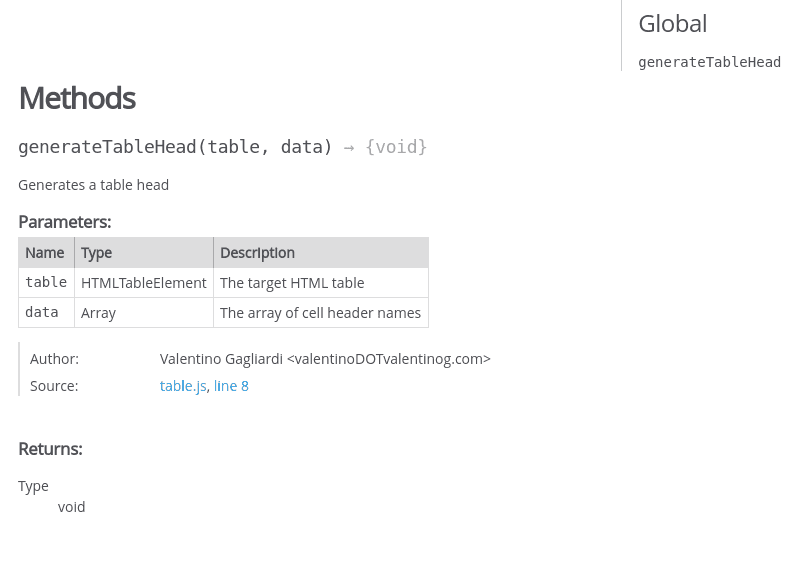

For specific languages, there are tools that allow structuring comments in a way that allows for generation of standalone documentation out of commented code.

Example (JSDoc for JavaScript):

/**

* Generates a table head

* @author Valentino Gagliardi <valentinoDOTvalentinog.com>

* @param {HTMLTableElement} table - The target HTML table

* @param {Array} data - The array of cell header names

* @return {void}

*/

function generateTableHead(table, data) {

const thead = table.createTHead();

const row = thead.insertRow();

for (const i of data) {

const th = document.createElement("th");

const text = document.createTextNode(i);

th.appendChild(text);

row.appendChild(th);

}

}

Becomes:

Driven to extreme, such approach culminates in the literate programming paradigm, where code is generated out of documentation mixing natural language explanations and code snippets. This is similar in concept to well-documented Jupyter notebooks.

If multiple people are working on the same software project, it's important to allow collaborators to skip reading "your" parts of the code if they only need to use it, not modify it.

Documentation that summarizes the purpose and usage of your code achieves this goal.

Code documentation's is of utmost importance in any upcoming code maintenance. People currently responsible for any specific piece of code can change (expectedly or unexpectedly) in the future.

Often, reading other people's code can be an unpleasant experience, especially if maintainability was not given enough thought.

Unfortunately, this lack of foresight for maintenance is not uncommon. So, code documentation often needs to be improved after the code is written and finalized. This is also true of user documentation.

Some types of in-code documentation are actually useful beyond being read by human eyes.

Writing an explanation of function purpose, parameters and return values in a specific format can enable code editors to display these as hints for the programmer while working on related code.

Meanwhile, metadata contained in such documentation can help editor features such as autocomplete to understand your code better, and provide a better experience.

This goes beyond editor hints; some languages have static analysis tools that can reason about code correctness based on this kind of metadata.

This is especially important for languages with loose type systems (e.g. Python, JavaScript), where some implicit information (e.g. "this function parameter is supposed to be a string") can be made explicit with type annotations for use in various tools, even if such annotations have no effect at program runtime.

User and developer documentation are very different goals.

For developer documentation, you can assume some familiarity with the tools used and systems described.

For software whose users are other developers (libraries and APIs), the documentation can be very technical.

For end-users, often a less terse, technical style is needed, and things obvious for a developer may need to be explained. This may require specialists that know users' problems better, which is often people who perform integration work.

And if your documentation is consumed by automated systems (e.g. documentation generators, static analysis tools), you need to adhere to syntax that's as rigid as another programming language.

The biggest challenge with documentation is keeping it in sync with the actual code it describes.

The closer to the code documentation is, the easier it is to remember to maintain it. This makes documentation generation systems especially attractive.

Once a particular part has been documented, it becomes a commitment to keep documentation up to date, because outdated documentation is actively misleading and worse than no documentation at all.

Documentation does not influence how the code runs. Therefore, it always seems like extra effort to write it: after all, software is supposed to work as the first priority.

But not writing documentation (or at least comments) always hurts maintainability, and is a form of technical debt that can cause problems in the long run.

User documentation is often critical for a program's usefulness, where less obvious features of the software can be explained directly instead of trial and error or word-of-mouth.

Time for writing and updating documentation should be budgeted in any serious software development effort.

Documentation is often the public face of an open-source project. It is one of the first things to look at when evaluating fitness of purpose and overall state of OSS projects.

A well-made and up to date documentation shows vitality and maturity of open-source projects, while non-existant, outdated or partial/uneven documentation is a warning flag.

Documentation is an often-overlooked way of participating in open-source software; original developers may not have time for the extra effort that good documentation requires, or may lack the skills for making one. In that case, contributing documentation can be a very welcome and relatively easy task for volunteers.